Leave the Leaves

By Reyna Williams

“Removing leaves may actually do more harm than good”

Each autumn, millions of households gather, bag, and dispose of fallen leaves as part of a seasonal ritual. While neat, manicured lawns have long been associated with suburban order and aesthetic appeal, growing ecological research suggests that removing leaves may actually do more harm than good. Fallen leaves play a crucial role in supporting soil health, biodiversity, and long-term landscape resilience. Leaving them in place, or managing them on-site rather than discarding them, offers environmental benefits that extend far beyond the property line.

Leaves are a natural form of slow-release fertilizer.

As leaves decompose, they break down into valuable organic matter, returning essential nutrients to the soil. Nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium are stored within the leaves during the growing season. When decomposition occurs, these nutrients become available to garden beds and trees. This nutrient cycling helps maintain healthy soil structure and fertility without synthetic fertilizers.

Moreover, the process of decomposition increases soil organic matter, which improves soil’s water-holding capacity, promotes aeration, and enhances its ability to resist erosion. Soils rich in organic matter are more resilient to drought, compaction (trampled on), and extreme temperature fluctuations—conditions that are increasingly common due to climate change

Fallen leaves create microhabitats that support a wide range of organisms essential for a healthy ecosystem.

Many beneficial species—including beetles, earthworms, fungi, spiders, and pollinator larvae—rely on leaf litter for shelter, overwintering sites, or food. For instance, several species of butterflies and moths spend the winter hidden in leaves as pupae or caterpillars. Removing leaves disrupts these life cycles and contributes to declining pollinator insect populations that help our food crops grow.

These small organisms are not just inhabitants of the leaf layer, they are active participants in ecological health. Earthworms, for example, feed on leaf litter, and their activity helps mix organic material into the soil, improving its structure. Fungi assist in decomposition, forming symbiotic relationships with plant roots that enhance nutrient absorption of plants. Leaving leaves in place directly supports these crucial ecological processes.

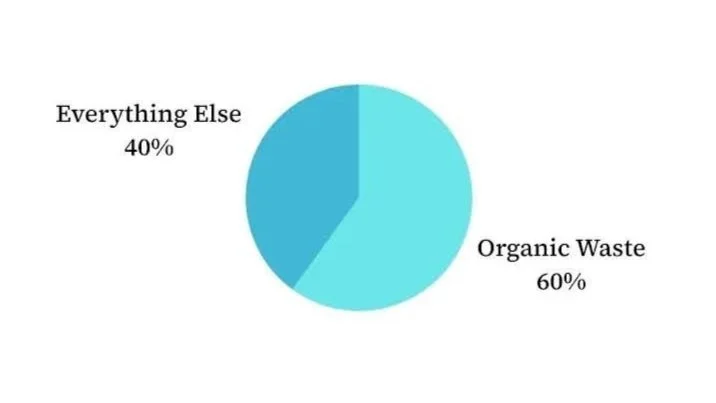

Bagging leaves and sending them to landfills contributes significantly to municipal waste.

In many areas, organic waste like yard debris makes up around 60% of landfill material. When leaves decompose anaerobically, meaning without oxygen, in landfills, they produce methane, a potent greenhouse gas. By leaving leaves in the yard or mulching them, homeowners help reduce their carbon footprint and alleviate pressure on waste-management systems.

In addition, using leaf blowers, particularly gas-powered models, to remove leaves generates noise pollution and harmful emissions. A gas-powered leaf blower can create as much smog-forming air pollution in one hour as driving a typical car for over 1,000 miles, because its simple engine burns fuel very inefficiently. Choosing to leave leaves in place (or mulch them with a mower) eliminates the need for this machinery, contributing to cleaner air and quieter neighborhoods.

A natural layer of leaf litter acts as a protective mulch.

It insulates the soil from extreme temperatures, helping plant roots withstand winter cold. It also conserves soil moisture by reducing evaporation, which can be especially beneficial during dry seasons. By buffering the soil environment, leaf cover supports root health and reduces stress on trees, shrubs, and groundcover plants.

This natural mulch also suppresses weed germination by blocking light from reaching weed seeds. As a result, homeowners can enjoy fewer unwanted plants without resorting to herbicides.

Do not overdo it.

Leaving leaves does not have to mean allowing them to smother the lawn. Thick layers of whole leaves can mat down and inhibit grass growth, but the solution is simple: mulching. Running a lawn mower over the leaves shreds them into small pieces that easily decompose and blend into the turf. This technique provides the benefits of leaf litter while maintaining a tidy appearance.

In garden beds, whole leaves may be left as is to form a protective winter blanket for perennial plants. They break down slowly and build rich, dark humus that improves soil structure over time.

The practice of removing fallen leaves is more of a cultural habit than ecological necessity.

By allowing leaves to remain on their property, whether whole in garden beds or mulched into lawns, homeowners help nourish the soil, support biodiversity and wildlife, reduce waste, conserve moisture, and create healthier landscapes. Embracing the natural cycle of leaf fall is a simple yet powerful way to work with nature rather than against it, fostering a more sustainable and resilient environment for future generations.